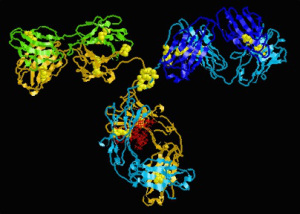

Example of an antibody.

Example of an antibody. Last week, Dr. Judy Van de Water of UC-Davis gave a talk about current research on immune system dysregulation in autism at theThompson Center here at MU. This talk came at an opportune time, as many debates have spurred from some recently published reviews on this topic. Dr. Van de Water presented some exciting findings, but, refreshingly, remained hesitant to overgeneralize their implications.

Throughout her talk, Dr. Van de Water illustrated potential relationships between the immune system and the development of autism. For instance, out of the hundreds of gene variants thought to be associated with autism, many are related to immune function. Also, studies have found alterations in the expression of these genes, as well as abnormal activation of immune-related brain cells and altered brain and cerebrospinal fluid levels of cytokines (immune-related signaling molecules), in autism.

Dr. Van de Water emphasized, though, that the data behind these findings represent the mean (or average) of individuals with autism, not the majority. These findings do not reflect the inherent heterogeneity (or variability) of immune function in autism. Dr. Van de Water expressed that while some individuals with autism may have a hyperactive immune system, others may have immune system deficits, and still others may have completely normal immune function.

Additionally, Dr. Van de Water presented findings related to antibody production and autism. Antibodies function as the body’s defense system against foreign substances and are upregulated in states of immune system activation. Some antibodies, called autoantibodies, may fight against the body’s own cells. In autism it seems there are higher levels of autoantibodies in certain brain regions, such as the cerebellum. This heightened antibody response in the cerebellum may be related to decreased cognitive abilities.

Lastly, antibodies may be related to the development of autism in utero, as some maternal antibodies can cross the placenta and affect fetal brain development. Some mothers of children with autism express a specific pattern of these antibodies. Interestingly, a polymorphism of the immune-related MET gene may lead to these altered patterns of antibody expression, meaning this MET variant may function as a susceptibility gene for autism.

At the end of her talk, Dr. Van de Water described a blog post she was asked to write for the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative website in light of the thought-provoking columnon autism and immune function published in the New York Times. In her post she emphasizes the heterogeneity of autism, and that “generalizing the findings [related to immune dysregulation] from one subtype or group to another can be dangerous where treatment is concerned.” As has been demonstrated before, the questions related to the study of autism greatly outnumber the answers. Instead of overgeneralizing the answers, we need to keep asking the questions.

[This post was originally published at my previous blog, Neurolore.]

Throughout her talk, Dr. Van de Water illustrated potential relationships between the immune system and the development of autism. For instance, out of the hundreds of gene variants thought to be associated with autism, many are related to immune function. Also, studies have found alterations in the expression of these genes, as well as abnormal activation of immune-related brain cells and altered brain and cerebrospinal fluid levels of cytokines (immune-related signaling molecules), in autism.

Dr. Van de Water emphasized, though, that the data behind these findings represent the mean (or average) of individuals with autism, not the majority. These findings do not reflect the inherent heterogeneity (or variability) of immune function in autism. Dr. Van de Water expressed that while some individuals with autism may have a hyperactive immune system, others may have immune system deficits, and still others may have completely normal immune function.

Additionally, Dr. Van de Water presented findings related to antibody production and autism. Antibodies function as the body’s defense system against foreign substances and are upregulated in states of immune system activation. Some antibodies, called autoantibodies, may fight against the body’s own cells. In autism it seems there are higher levels of autoantibodies in certain brain regions, such as the cerebellum. This heightened antibody response in the cerebellum may be related to decreased cognitive abilities.

Lastly, antibodies may be related to the development of autism in utero, as some maternal antibodies can cross the placenta and affect fetal brain development. Some mothers of children with autism express a specific pattern of these antibodies. Interestingly, a polymorphism of the immune-related MET gene may lead to these altered patterns of antibody expression, meaning this MET variant may function as a susceptibility gene for autism.

At the end of her talk, Dr. Van de Water described a blog post she was asked to write for the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative website in light of the thought-provoking columnon autism and immune function published in the New York Times. In her post she emphasizes the heterogeneity of autism, and that “generalizing the findings [related to immune dysregulation] from one subtype or group to another can be dangerous where treatment is concerned.” As has been demonstrated before, the questions related to the study of autism greatly outnumber the answers. Instead of overgeneralizing the answers, we need to keep asking the questions.

[This post was originally published at my previous blog, Neurolore.]